"I’m a lady MacGyver"

Julie Beck is an incredible painter from Boston, Massachusetts. Her realistic portraits and still-lifes explore themes of identity, relationships, and nostalgia. She's won a gold and silver medal from the Guild of Boston Artists, and has been a finalist in several Art Renewal Center shows. She came in 3rd at the 2017 Grand Central Atelier's still life competition.

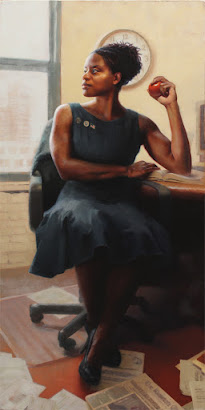

'Conservation of Energy (Selfie)', 2015

Julie Beck was born and raised in upstate New York. She first studied mathematics, graduating from Roger Williams University, where she was class valedictorian. She spent the next decade working as a freelance designer, and taught herself to paint in her free time. From 2011-16 she attended the Realist Academy of Art in Boston, where she now teaches. She talks about it in

this interview with Antrese Wood for the Savvy Painter Podcast (no date):

“My school, which I do have to give a plug to, is the Academy

of Realist Art in Boston, and it completely changed my life. The minute I set

foot in there I drank the Koolaid, and I was in, and I love it. And, it

basically gave me the freedom to make the work that I want to make. Because,

before that I didn’t know you could actually be taught this stuff. I just kind

of assumed you either had it, and you just knew how to paint. All my experience

had been self-taught. I didn’t know ateliers existed. And I’d taken a bunch of

classes at some CE places, and I was so disappointed because no one was

teaching me how to make this really highly technical work. So, when I first came

to ARA Boston and I walked in, it was like, ‘They could tell me to shine their

shoes and I would do it. If I can paint like that, whatever they tell me to do

to learn how to paint like this I will do that.’ So they became a second home

to me. They’re my family. They’re my friends. They’re the people I spend the

most time around, other than my husband, obviously, but I’m sure, If he could

be there then I’d be there 24 hours a day. But, it’s a wonderful place, and we’re

all so passionate. So ,I’ve been teaching there, and I’ve been the assistant

director there. And the most wonderful thing has happened which is, yes, we did

get an additional floor. Which means, we can have more students, but it also

means I have my very first studio room to myself. I can actually spread my arms

and my studio space is wider than that. I can have two still lifes going at

once, it’s a luxury.”

'Creation of Eve', 2018

"Humans have an innate desire to connect with others. Representational visual art provides a common language that transcends spoken language, geography and time. My commitment to creating accessible and relatable work is an expression and celebration of this desire to connect. I hope that my work can inspire others to discover or rethink their perspectives about themselves and their surroundings, as this is the gift that painting has offered me."

'Are We Men, Or Are We Comets?', 2017

"I have 2 very different conceptual approaches. One for Still Life, and one for everything else. Portraits/figures/animals start with a very specific idea and the painting is designed around that concept. There is usually a very clear direction from initiation. Still life paintings, however, are a form of “play” or “happy accidents.” They start with pairing colors or textures. With different groupings of objects, which can sometimes take weeks to find, a narrative or relationship emerges organically. This is where I “find” the painting. Because I mostly work from life for these, once the set-up is complete, all I have to do is paint. As these two categories of animals/figures and still lifes challenge me in different, but equally important ways as an artist, I work on them simultaneously. Across both categories, however, composition, design and narrative are paramount. No aspect of the picture is ignored."

'Red Hand, Green Thumb', 2017

Julie talks about her work 'Red Hand, Green Thumb' (Wood, no date):

“That

painting was a total accident, and it didn’t happen on purpose, in a way. I

work from both life and photos, and I’d taken a whole bunch of photo shoots of

a student and friend named John. And, I ended up with two pictures, one of ‘em

ended up going into ‘Are We Men or Are We Comets’, which is the painting it was

intended for. But, I had kind of a one-off that I thought was really interesting.

So, I kind of kept it off to the side. And, then I ended up going on an artists’

retreat . . . It

was a complete departure from my normal process. . . . I normally work in a

very controlled process. Everything is planned, and by the time I get to

painting, I’m ready to go. I usually finish 95% of the paintings I start

because so much work goes into it before any paint goes onto the canvas. So, I brought a completely blank canvas, and that is super

scary. So, I brought this reference image and a blank white canvas, and I had

no plan. . . . There’s zero control over the situation . . . and I’m working alongside some of the most

incredible artists. I was invited along this retreat with, I don’t know if you

know Julie Bell and Boris Vallejo? These people are amazing, and this is the

first time I was invited, and I don’t want to look like an amateur, I wanna be

a professional, but at the same time I want to get outside my comfort zone. So,

that painting I started straight out of the canvas with paint – totally unlike

me. I had no plan for the background, no plan for an environment, I just

started going for it . . . but, like so many on your podcast said, getting

outside your comfort zone and doing something scary is a huge opportunity to

grow and discover new processes, or just seeing something new and discover more

about you in the process. So, that painting is interesting to me because it’s

such a departure . . . but I learned so much from it and it allowed me to be

more daring and risky. And I have to say, and it sounds so ridiculous when you

see this painting - every one of those bold brushstrokes in the background was torture.

Total torture, because there’s no right or wrong. There’s no rules and that’s

very uncomfortable.”

'A Vessel with Two Hands', 2019

Julie says (Wood, no date), "I love titling paintings, it’s one of my favorite parts of

creating something. I have a list of orphan titles, so I’ll come across a

phrase or something that’s really intriguing to me, or if I’m reading a book,

and there’s a little line that catches me. . . . I've had a couple paintings where titling it made it completely different experience for me.”

'The One You Feed', 2015

"I

hate signing paintings, it takes me, like, a year. Part of it was I never had

anything consistent, and when I did do it, it always looked so weird, and I

hated it. So, I was like, Screw this, I’m making a rubber stamp.’ So, I actually

used to be a graphic designer, I spent ten years doing graphic design and

editing, and stuff like that. But, something that I feel I got out of that was

being graphically proficient. And, so I said, ‘I’m going to make this in

Illustrator, I’m gonna make a rubber stamp out of it.’ It’s a shapy thing, it’s

related to squares. And, I just want this little simple – my last name is four

letters, it’s really easy, and I just use a rubber stamp. Sometimes I have to

clean it up a little bit, but it’s so much easier.”

'Silas', 2013

“I

would say I’m a creative person in that I’m like a MacGyver. I’m a lady

MacGyver (laughs). It’s true, I’m really good at taking existing things and

making them into new purposes or combining things that already exist. I went to

school for construction, engineering and math, so I like when things work in a

really efficient way, or by taking existing things and making it work for me.

Which, I think that is kind of the basis of creativity. But, in terms of, I

guess, hippy-dippy kind of creative, artsy ideas, I don’t know if that’s my

natural tendency."

'Lydia the Lawyer', 2016

Julie gives this advice to anyone starting an art career (Wood, no date):

“The one thing I’d say has helped me the most is to take

myself seriously. When I first decided that I was going to be an artist, like

for real, for real, I made a folder on my computer and I titled it ‘I am an

artist.’ And, every time I made something, or I took a picture of a painting I did,

or I made a spreadsheet for something, it went into that folder and I had to

look at that, and remind myself I am an artist, and this is what I’m doing. And

so, by taking myself seriously, all the income I make through any type of art,

I report that. I take it seriously. This is my job. And, I think by doing that

it also forces me to also treat it like a job. This is my responsibility. I have a responsibility to make the work I

wanna make, to put it out there, and to stay organized and on top of

everything.”

'Girl Interrupted', 2014

Julie Beck has been so kind as to answer some questions about her life and work. So, here is our interview:

1. Can you tell us about your childhood? What did your parents do for a living? Did you have any siblings? Are there any other artists in your family?

"I didn't grow up in an artsy family. We were blue-collar, just-getting-by people."

'Saturday Morning Cartoons', 2014

2. How were you introduced to art, and when did you realize you have a skill for it?

"My only exposure to art was the typical stuff kids get into and that parents give their kids for activities, as well as public school art classes. I kind of always just knew I wanted to be a painter. I didn't think it was a realistic goal or achievable, but I knew I wanted it. I actually don't have a ton of natural talent. I think that's part of the problem in our society with our view of visual art- we give the message that if you're not naturally good at it then it's just not your thing. But the reality is that visual art CAN be taught, especially working representationally. We don't have the same view of music, dance, or other creative fields... but visual art is often seen as something that has no "rules" or fundamentals to train."

'Not My Circus', 2016

3. What led you to study math and engineering at university? A common theme on my blog has been to see so many extraordinary artists being pushed away from their creativity, toward more ‘practical’ or ‘important’ work. Were you pressured to steer clear of art?

"I love math and science. I wasn't pushed away from creativity as much as I also loved math and science and it's a more logical path for a profession if you don't want to struggle to make ends meet. I was still encouraged to pursue art and creativity but to build it alongside something else that was more financially reliable. I think this is the responsible thing to do and I would encourage younger people to do the same. Making art your only source of income right off the bat can make things harder than they need to be (unless you have other means of making ends meet. Some people have trust funds, or other people supporting them, so this would not apply to them.) Yes, it may feel like a "distraction" but I have learned to appreciate that I don't have to freak out if a painting is taking longer than I wanted it to, or I'm not feeling as artistically productive as I want to be. Staying true to your artistic voice is kind of hard when you're worried about selling paintings to pay rent."

'Down by Killarney's Green Wood', 2015

4. You graduated valedictorian in math, but went straight to graphic design as a career? Did you never do any engineering work? Or teaching math? Surely, you could’ve, no?

"During college, I needed to work and my senior year I was able to get an internship at a company that I had a connection in. I had 2 choices for departments. One was in the actuarial department, the other was in the Creative Services department. Since I thought it was temporary, I went with the one that sounded way more fun. From there, I was fortunate to have one of the best managers ever. I expressed the desire to maybe learn photoshop and he immediately threw me my first assignment. That led to 10 years of graphic design, motion graphics, and video editing."

'Evidence of Presence', 2012, reworked 2020

5. How and when did you meet your husband, and what does he do?

"I do not give out info about my partner."

'Sometimes A Banana Is Just A Banana', 2019

6. One of your paintings, ‘Sometimes a Banana is Just a Banana’, takes aim at Maurizio Cattelan. What’s your stance on conceptual art, and who do you blame more, the artist who tapes a banana to a wall, or the people who spend $120,000 on it?

"'Sometimes a Banana is just a banana' is not actually a commentary on the original work. Using the pop-culture imagery of the banana taped to a wall, I used a combination of both the current work and the historic Rene Magritte painting 'The Treachery of Images' to force the viewer to ask themselves certain questions. My work is often very realistic and tromp l'oeil (meaning to fool the eye). So why make work that looks to create an illusion of reality? Often people will ask me 'why not just take a photo?' Or, 'What's the point of painting it exactly the way it looks in real life?' People still question the validity of making highly realistic artwork. By making this painting that is so realistic, I am forcing the viewer to ask themselves a few things. Combined with the phrase at the bottom, 'This is not art,' it begs the questions: is the painting itself not really art because I just made something that looks exactly like reality? Is it reality and not actually a painting, meaning it's not art? How do we decide what IS art? The Rene Magritte pipe painting tells the viewer that his painting of a pipe is not a pipe. It IS a pipe in that it's a representation of our understanding of the pipe, but we can't smoke out of it. So it IS a pipe but it is also NOT a pipe. The duality and actuality of reality is something I love to play with."

'A Match is Dropped', 2015

7. Are there any post-modern/conceptual artists you respect?

"I'm not sure what genre of painting this covers. I love tons of artists working today. I'm not well versed in art history."

'The Jupiter Moon'

8. Recently you’ve been painting over your older works – sometimes adding abstract/cubist backgrounds, and sometimes mimicking graffiti over them. What was the inspiration for all this and how do you feel about it?

"I couldn't work from life for part of the pandemic (my studio is at my school) so I was trying to figure out what I could work on at home. I have plenty of old work sitting around and I thought it would be a fun experiment."

'Nature vs. Nature 1', 2016

9. Do you see a difference in how you’ve painted over your works, and how, say, the Chapman brothers painted over Goya’s etchings?

"Again, not familiar with art history, so I'm not sure. It doesn't really feel any different to me except for the fact that I have the limitation of what was there before and how I want to adjust it without covering it completely. There's also the concept of 'time' involved here too I guess."

'Bones in the Ground', 2015

10. Who were some of your best art teachers and what did they teach you?

"My training at the Academy of Realist Art Boston and the teachers there was life changing."

'They That Sow The Wind', 2017

11. What do you worry about in terms of composition when you paint?

"Composition is EVERYTHING. Literally every item, object and space is thoughtfully considered before I ever begin painting."

'Flawless', 2014

12. How do you define great art?

"There is no definition of great art. It's subjective to the viewer. The art I love the most makes me stop and reconsider my view of the world.

"Great art for me personally: I could give you my list of top pieces of art that I love, but I think there are a ton of works that are great that I don't love. The classic example is of the DuChamp "Fountain" urinal. I hate it. But when I think about it in the context of a timeline where people were asking questions about what art IS and being told what art SHOULD be, the urinal is one step in series of important questions/statements. And it's a logical stop along the way in the sequence of responses to those questions and statements. Out of that context, I hate it. However I would argue that it is great in the context of the human exploration of expression and creativity. Artists from the past that I personally love their work include Charles Sheeler, Van Gogh, Rene Magritte, and my all time favorite is Norman Rockwell. There are others who I think have reached the pinnacle of technical ability in their chosen process but their content is not personally my thing, and others I admire for their unique creative voice. In visual art, so much is subjective and "great" can have multiple definitions."

'Midnight Message', 2016

13. If you could change anything about art education in the US, what would it be?

"Make observational technical training a part of the curriculum."

14. What advice do you give to young art students?

"If you're not naturally great or good, that doesn't matter. Find someone who does what you want to do who can teach it to you. Don't be afraid to reach out to artists you admire and ask questions. The person who is OK at something but works their [butt] off will overtake the person who is great but is not willing to put effort in, or to push themselves out of their comfort zone. Also, nurture a skill you can use to pay the bills. It's better if it's related to art in many ways like teaching, framing, working at a gallery, etc. but if it's not, that's OK too. That side gig can give you the freedom to make TRULY genuine work because you're not worried about sales to live. You have to decide for yourself if you are willing to create focused on sales or not. ART IS A BUSINESS, LEARN HOW TO MANAGE A BUSINESS, UNDERSTAND TAXES, KEEP SPREADSHEETS AND RECORDS. If you want to be an artist, you also have to be a business person."

15. What do you tell someone who thinks that art doesn’t matter?

"In the grand scheme of everything, art doesn't matter. None of this matters. We're on a giant rock flying through space."

Comments

Post a Comment